Neuroscience: The Good, the Bad, and the Transcendent. Part 2: Dualism and Non-dualism

As neuroscience has turned its attention to

feelings,

consciousness,

the self,

it has become clear that a lot of simple everyday concepts

that we all (scientists too!) assumed were valid—

—are not good descriptions of what is really going on in the mind and brain.

This is HUGE. These insights, although hard to digest,

point towards a whole new way of experiencing.

For instance, basic concepts like

“perception”,

“action”,

“thought”,

“emotion”,

“I”

“it”

turn out to be flawed.

Stunning! Who’d‘a thunk?

These concepts separate and distort the underlying reality,

These concepts separate and distort the underlying reality,

which does not divide things up into separate categories like this.

These categories are relics of a dualistic way of thinking.

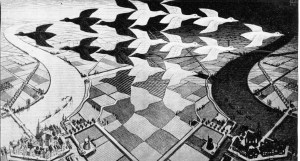

(Image: Birds by M. C. Escher)

We need to find a different way.

Another example of the dualistic bias of our conceptual mind.

is the tendency to think of the brain/mind as modular,

with separate regions performing separate specialized tasks.

This is only a small part of the story.

In reality, The brain/mind operates as a coherent whole,

Not separate from body and environment;

more like an orchestra, or the ripples on the ocean

than a machine or computer.

The more awake you are, the more connected the brain is;

this means that large areas vibrate at the same or similar frequencies,

this is the same principle behind musical chords that sound pleasant (consonant).

In addition, the more awake & balanced you are,

the more brain activity hovers

“on the edge of chaos”;

poised between too much order & too little,

at the “Goldilocks” place!

This “Natural State” is inherently pleasant, just like a resonant chord. (On the left: Antique Sound, by Paul Klee)

This “Natural State” is inherently pleasant, just like a resonant chord. (On the left: Antique Sound, by Paul Klee)

Moving into this connected state

necessarily must involve mind, feelings and body;

separating them inherently reduces connectivity!

When the whole system works without obstruction, we call this the Natural State.

In this state, we are fully connected, acting effortlessly & spontaneously, without inner conflict, and fully integrated with the environment.

Unfortunately, we are not often in this state!

Everybody gets in their own way, more than we realize.

The essence of Bodymind Training is

to learn how to let go of interference

and move towards the Natural State

in all situations of life.

Below is a little map:

Through Bodymind Training

we can move into the Natural State directly

through experiencing the wholeness of our being in the moment:

Standing solidly on the earth,

floating lightly towards the sky,

open to what is all around us.

More about this “map” to come–stay resonant!

There is a lot of “Neuroporn” out there:

There is a lot of “Neuroporn” out there:

Gravity:

Gravity:

work with first responders, particularly police. With a background in law enforcement, he has “street cred.” He is currently involved in a fairly large clinical trial of Qigong for first responders, which is wonderful! How long will it be, I wonder, until this is standard training?

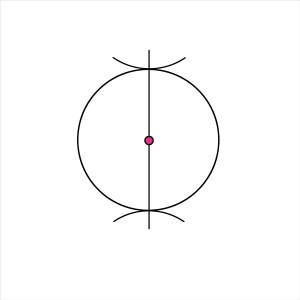

work with first responders, particularly police. With a background in law enforcement, he has “street cred.” He is currently involved in a fairly large clinical trial of Qigong for first responders, which is wonderful! How long will it be, I wonder, until this is standard training? ce, just bringing the attention to your center of gravity (just below the navel, in the middle of the body) will immediately move you towards a calmer, more alert state, ideal for handling crises. (My “right instruction” comment covers how exactly to locate the center, when this practice is NOT a good idea, and the difference between paying attention TO, and paying attention FROM, this region of the body.) Contemplate the sketch to the left, and feel what happens in your body.

ce, just bringing the attention to your center of gravity (just below the navel, in the middle of the body) will immediately move you towards a calmer, more alert state, ideal for handling crises. (My “right instruction” comment covers how exactly to locate the center, when this practice is NOT a good idea, and the difference between paying attention TO, and paying attention FROM, this region of the body.) Contemplate the sketch to the left, and feel what happens in your body. a Chinese Qigong Master now living in New Mexico. I had heard of him before, and was deeply impressed with him in person. He radiated happiness and well-being, but not in an obnoxious or oblivious way; he is very aware of the need to embrace all experience, the painful and the pleasurable both. In the few personal interactions I had with him I felt that he was authentic and genuinely present. He was very generous with his time and his teaching, and is actively using the web to make his teaching more widely accessible. Dr. Gu shares our interest in developing videos to teach qigong and Bodymind Training—he told us, “Everything can be taught by video!” And we hope to prove him right!

a Chinese Qigong Master now living in New Mexico. I had heard of him before, and was deeply impressed with him in person. He radiated happiness and well-being, but not in an obnoxious or oblivious way; he is very aware of the need to embrace all experience, the painful and the pleasurable both. In the few personal interactions I had with him I felt that he was authentic and genuinely present. He was very generous with his time and his teaching, and is actively using the web to make his teaching more widely accessible. Dr. Gu shares our interest in developing videos to teach qigong and Bodymind Training—he told us, “Everything can be taught by video!” And we hope to prove him right! precociously intelligent and bookish child, I was picked on at school. My half-brother Kenny, 10 years older than me, suggested Judo. I loved it! Something about the rituals, the language, the accoutrements, and above all hints of mysterious energies, drew me in. To the right: me at age 12, demonstrating with my long-suffering younger brother!

precociously intelligent and bookish child, I was picked on at school. My half-brother Kenny, 10 years older than me, suggested Judo. I loved it! Something about the rituals, the language, the accoutrements, and above all hints of mysterious energies, drew me in. To the right: me at age 12, demonstrating with my long-suffering younger brother!

You must be logged in to post a comment.